Lean into complexity when building vertical software

There’s inherent complexity in any vertical software play. That’s why it’s an attractive opportunity - you can solve a problem, and build a moat! Most software aims to hide complexity from users, or abstract it away. I’m of the opinion that given inherent complexity cannot be destroyed, expert users generally do not want it hidden.

Vertical software inverts this tendency to hide complexity. You understand the workflows and the objectives deeply, you standardize your software around them. Yes, our clinics want some customization - but we tightly control what is customizable to keep our general product complexity legible.1

This becomes a competitive moat

Competitors can’t easily copy your work because they can’t replicate the deep domain understanding that created these workflows. It’s not just code, it’s accumulated knowledge about edge-cases, about what your experts actually need vs what they ask for, about which complexity is domain-essential vs accidental - either in your processes, or theirs.2

The experts who embrace your complex tool become your advocates and your best source of feedback. They understand why the complexity exists because they live with the underlying complexity of their domain every day. They appreciate that there are tools that meet them at their level - just like you do when designing or writing code.

I wrote this while working at wawa fertility3, where we build software for fertility specialists to do their best work. Don’t be too surprised when I start popping in examples about IVF!

As simple as possible, but no simpler

When you’re building specialist vertical software, you quickly discover that experts and beginners need fundamentally different things. Beginners need simplicity. Experts have much more nuanced expectations based on the inherent complexity of their work.

This creates the central tension in most complex software: the features that make experts productive often make beginners feel overwhelmed. There’s a tendency to default to the simple, easy to adopt way of doing things, but when building vertical software, I believe this is a mistake.

I’ve seen this play out poorly. CRM’s that are configured to be “easy to use” that have created a birds nest of automations nobody understands, in an attempt to fill in the gaps. Datasets that are “simplified” and then gloss over some nuance that’s valuable to the end user. Workflows that turn a quick task into a maze of guided wizards.

All users are willing to learn complex tools if those tools make them more effective.A nuclear power station control room looks intricate. So does a plane’s cockpit, a CNC machine, 3D modelling software. It’s easy to fall into the trap that this isn’t necessarily “good design” because it’s not immediately accessible. Too many buttons, too much information. To the operator, it makes perfect sense. Every control exists because removing it would make the operator less informed, less immediately capable, and thus less effective. It’s about speed, clarity, confidence in the full overview before making the next move.

You should internalize that complexity can only be moved, not eliminated.4 They’d rather see the complexity than have it hidden from them. Are you optimising for the first hour of use, or the 40th?

Training approaches

Here’s what separates expert-focused software from consumer software: there’s dedicated time for training. Training almost feels like a dirty word in UX circles - your product isn’t simple enough for people to intuitively understand?

Easy to use is not the same as easy to learn. A complex system should still be easy to use.

Expert software optimizes for 40 hours of use a week. The trade-off we’re making when we prioritize expert-user performance is that we’re investing more time in training and education.

That’s not to say everything requires training. There are multiple dimensions to these things - pick the one that’s appropriate. Simple things should be simple, complex things should be possible. So how do we break that down? It’s going to sound obscenely simple but these things tend to be. If your model of the world is not familiar to your end user, they will require more training. It’s our job to figure out which bits of the product fit into which buckets.

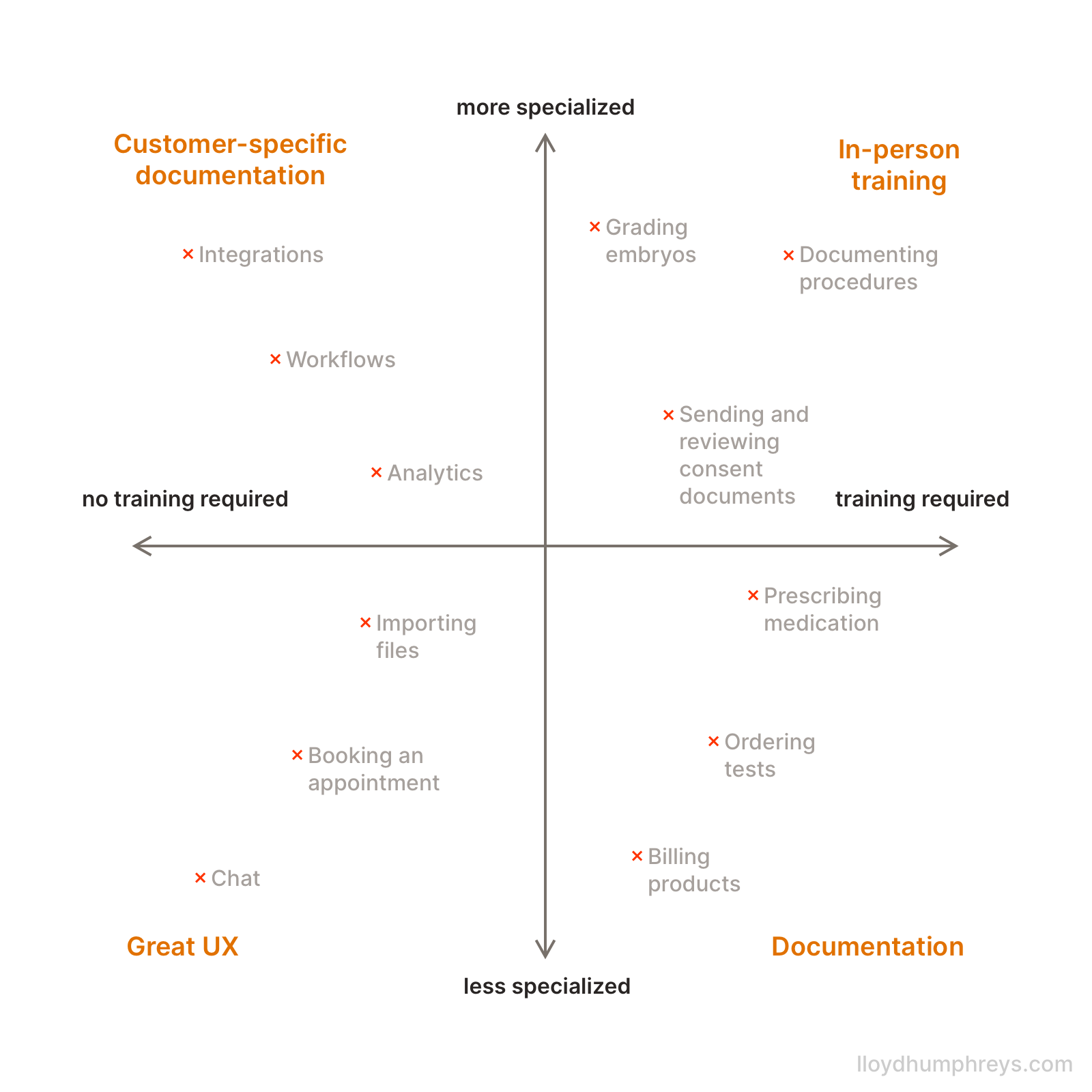

Here we see how I’ve applied this to wawa work:

Less specialized

If it’s intuitive, it is easier to learn and subsequently requires less training. But we must divide this into:

- tasks that are inherently intuitive - everyone knows how a Chat works

- tasks where the industry model is intuitive, but our product needs some explaining.

Prescribing medications is a good example of the latter. It’s pretty complex - but in the industry, people are familiar with it and understand it intuitively. In our system, there’s additional complexity - there are permissions, PIN-code setups, etc. so if we document those things well and can point you in the right direction, you’ll figure out the details.

More specialized

These things tend to be less intuitive. As part of rolling out our tool, we integrate into lots of different hardware and software solutions. Anything that interacts outside our system is inherently confusing to an end user, and we can’t expect them to figure it out. How that all works, debugging and maintenance - requires customer specific reference documentation, but perhaps not so much active-training. On the flip side, there are specialized activities - where professionals who perhaps didn’t collaborate before now can because of the integrated nature of our system, or have to learn how we’ve standardized things from our specialist industry knowledge.

How this manifests in what you build

When you’re selling to experts, handling the complexity becomes a selling point that resonates.

Power users are your target audience

Your expert users will push your software to its limits. The complexity that serves power users and edge cases well often makes the software better for everyone.

We had discussions with embryologists running treatments with multiple donors. Other systems forced separate ‘cycles’ for each donor breaking you into different screens, duplicating data entry, making reporting a challenge.

The simple approach would be: this is an edge case, let’s not complicate things.

But here’s what we learned: the features that serve edge cases well often simplify the mainstream cases too . By supporting multiple donors natively, we eliminated the cycle-splitting workaround entirely. Now reporting is simpler for everyone because all treatment data lives in one place, regardless of donor count.

In sales demos, we skip that simple flow entirely. We demo multiple donors - the most complex scenario - because it proves we really understand the domain in 5 minutes.5

Embrace density

Don’t hide functionality. Experts want to see everything they can control. Make it denser: put more stuff on the page. Don’t hide things, don’t make me click or hover or load a new page.

If you need to put lots of things on the page, you pick up new design directions. Grids, tables, contrast, color-coding - all becomes more important when there are more things happening. Go deep on those primitives rather than inventing new ones.

Aggressively remove interactions/clicks

Run through a core flow and think: could we remove a click? I know this sounds basic. But if you’re doing this flow multiple times a day, you start to get annoyed.

- Could this dropdown be a radio button?

- Could we default this option based on some knowledge we have?

- Can we default this to the pareto-value, so I can interact with it less?

- Is defaulting this value dangerous, if the user isn’t paying attention?

When you get really demanding about this, you get creative. At wawa, we noticed people were creating lots of folders; so we made it possible to comma-separate the names to create multiple folders at the same time. A tiny change, zero UI beyond a placeholder hint, hundreds of interactions removed per staff member per week.

You’ve got to sweat these details. If you really understand what your user is trying to solve, you can’t help it - you see how every little thing creates friction that compounds into problems for your users and their goals. Eliminating friction compounds too!

Documentation is design

Since experts expect training, your documentation becomes part of the product experience. Fantastic onboarding isn’t about making things simpler - it’s about making the complexity approachable.

- Great documentation

- Tooltips, nudges in the product

- If your product is very “busy” - empty states become confusing. Make it really easy to get things to an actionable state

This should extend to your marketing

This philosophy must extend beyond product into marketing. Dumbed-down content alienates experts; they can tell you don’t understand. Your marketing should demonstrate domain expertise. I’ve got many more thoughts about this, I’ll save them for a future post!

Challenge yourself when building

- Are we hiding complexity that experts need to see, or genuinely eliminating accidental complexity?

- Would a power user choose this simplified version over the complex one, given the choice?

- If we removed this feature tomorrow, would experts build a workaround?

- Are we making it easier or harder to make mistakes?

- How can we make it easy for our power users to teach others about this?

- If people are regularly asking to export to Excel - this is a flag that something is missing and they’re working around a limitation

Meet experts at their level

The experts who embrace your complex tool become your advocates, your feature-requesters, your competitive moat. They understand why the complexity exists because they live with it in their domain every day.

If you’re building vertical software, stop asking “how do we make this simpler?” Start asking “who is best positioned to handle this complexity?” Often, the answer is: your experts. They’re already managing this complexity in spreadsheets, workarounds, and manual processes. Hiding it is a hindrance.

Give them a tool that respects their expertise. They’ll reward you with detailed feedback and referrals to peers who understand why your ‘complicated’ software is actually exactly what they need.

Further reading

- No Silver Bullet - Fred Brooks

- Tesler’s Law - Larry Tesler

- Are you in feature hell? - Matthew Wensing

Footnotes

-

As Alan Kay said: “The right abstraction is the difference between people being able and unable to manage a system.” ↩

-

This nuance does make it somewhat harder to onboard new colleagues to your engineering team! ↩

-

Fertility specialists keep track of eggs collected, embryo development, genetic testing results, cryostorage inventories… all manner of detailed, nuanced work! ↩

-

Todo: write this article on abstracting away complexity ↩

-

An embryologist once asked me if I was a trained embryologist - best compliment I’ve received in my career! ↩